Change Management.

-

The Power of How

Successful organizations master the how.Focusing on execution excellence can make all the difference for your organization.

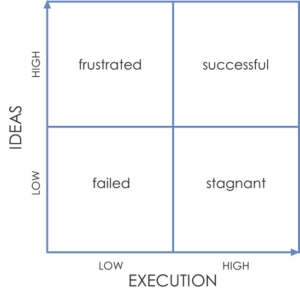

Take a look at this matrix. Where would you place your organization?

Clearly, this grid says successful organizations need both brilliant ideas and excellent execution. But what if you land in another quadrant?

For today, let’s focus on the EXECUTION axis. Some organizations are fantastic at defining why they exist and what they want to achieve. Mission statements are clear, goals are ambitious, and the vision is inspiring. They’re high on IDEAS. Yet, when it comes to executing these grand plans, they falter. They’re low on EXECUTION, so they land in the “frustrated” quadrant.

The missing piece? A focus on how to get things done.

Keys To Mastering the ‘How’

- Turn strategy into action. Every organization sets out with clear objectives, whether it’s increasing market share, driving innovation, or improving customer satisfaction. But these objectives can only become reality if there’s a solid plan in place. Focusing on the how means you’re not just setting lofty goals, but you’re also laying out the step-by-step process to achieve them. It’s not enough to know where you want to go—you need a map to get there.

- Improve consistency. Many companies achieve success on a small scale but struggle when trying to expand. Why? Because they haven’t standardized processes. When you focus on how things are done, you have a standard approach that works across the board—in different departments, locations, or even countries. This consistency helps you scale without sacrificing quality.

- Become more agile and adaptable. The only constant in life is change. Companies that focus on how they operate are better positioned to adapt quickly to new challenges. When you know the steps that lead to success, it’s easier to tweak them as the landscape shifts. A strong focus on the how makes your business more agile, allowing you to respond to market changes and stay ahead of the competition.

- Establish a culture of accountability. A clear focus on the how fosters accountability. When every team member understands the processes behind the outcomes, there’s a shared responsibility for both successes and setbacks. The ‘how’ creates a sense of ownership, as everyone knows their role in executing the plan and contributing to the company’s success.

- Build trust with clients and stakeholders. Clients and stakeholders don’t just want to hear about the big promises your company is making—they want to know how you’re going to deliver. When you can clearly explain your processes and show them that you’ve got a reliable system in place, it builds confidence. Focusing on the how shows that you’re not just talking the talk—you’re walking the walk.

When companies focus on the how, they unlock benefits that drive long-term success:

- Increased Efficiency: Well-defined processes reduce redundancy, creates efficiencies, and eliminate bottlenecks. This not only saves time and resources but also ensures projects stay on track and on budget.

- Consistent Quality: A well-defined how ensures that every project, product, or service is delivered with the same level of excellence. This builds trust with your customers and strengthens your brand.

- Improved Employee Engagement: When people understand how their work contributes to the bigger picture, they’re more motivated and engaged. They feel connected to the company’s goals and take pride in their role in achieving them.

- Data-Driven Decision Making: When you focus on how things are done, you’re more likely to collect data on your processes. This data gives you valuable insights into what’s working and what’s not, allowing you to make smarter decisions moving forward.

How To Master the ‘How’

To successfully shift your company’s focus to the how, consider these practical steps:

- Examine your current operation. What are your key processes? How are they documented and communicated? Are there gaps in execution? Analyze your team structure and capacity. Build an accountability (RACI) chart to drive ownership and progress. Understanding where you are now is the first step to making improvements.

- Prioritize. If you’re light on execution, it’s best to focus energy on the most impactful processes. Determine the business value of key processes and rank them; consider a grid showing ease of execution vs. impact, to identify both the highest value processes and the “low-hanging fruit.”

- Use technology. Technology tools can automate repetitive tasks, track progress, and manage workflows. Find the right tech to support your processes and make work more efficient.

- Create clear roadmaps. Create a roadmap for each high-priority process, showing how it will be done going forward. Make sure each step is clear and assign roles (on your accountability chart). Then share, so everyone knows their responsibilities.

- Invest in your people. If you’re launching a new focus on process and accountability, that’s a change for employees. They need communications and engagement activities so they understand roadmaps and adopt the new direction. And, of course, they need the skills and knowledge to execute the how Regular engagement learning are essential to execution excellence.

- Build in feedback loops. Regularly collect feedback from employees, clients, and stakeholders to learn how processes are working. This feedback is crucial for continuous improvement.

It’s easy to get caught up in the big picture—the what and the why of your business.

But without a clear focus on how you’re going to achieve those goals, even the best plans can fall short.

When you master the how, you’re setting your business up for long-term success.

-

The Sunk Cost Problem for Change Projects

Learn four organizational strengths to protect against the sunk cost fallacy.Why is a project over budget and years-delayed still going?

Imagine it’s movie night. You drive to the movie theater, choose a movie, pay for your ticket and buy popcorn and soda. The movie starts but, forty minutes in, you’re pretty sure you don’t like it. What do you do? Most likely, you’ll continue watching.

Humans will continue with something we have already invested in — whether that investment is time, effort, or money — even faced with evidence that it is no longer the best option. It’s called the “sunk cost fallacy;” people stick with a course of action because they have invested in it, even when it’s clear that abandonment yields more benefit.

As the pace of decision-making increases, due to industry and economic shifts, sunk costs plague the corporate world.

Why is the sunk cost fallacy so damaging?

Do you remember this major business blunder?

Blockbuster considered buying Netflix but decided to double down on investing in physical rental stores when digital streaming started.

Blockbuster highlights how commitment to bad decisions can escalate to a failure of fundamental strategic goals. Ultimately, their loss of money, time, and effort were not survivable.

Even when failed initiatives don’t scuttle the company, they can do a lot of damage: weakened market position, opportunity costs, resistance to change, turnover, and demotivated employees.

How do we get stuck in these projects?

The core problem is that, for whatever reason, organizations fail to acknowledge that whatever time, effort, or money has spent to date is unrecoverable — hoping that additional resources poured into the project might yield the desired financial results. But how does that happen?

Bad planning underpins many failed projects. How can you meet ROI if you don’t know the “I”? Once optimistic budgets are blown or unrealistic milestones are passed, the project is adrift. Often, project leaders just nudge budgets and schedules, hoping to minimize the magnitude of the failure, rather than starting over with a fresh eyes and lessons learned.

Bad planning underpins many failed projects.

Personal involvement of leaders in projects is a double-edged sword. We need leaders to wholeheartedly sponsor important initiatives if they are to succeed. However, this personal connection makes it hard to admit that a pet project is headed for failure, and even harder to pull the plug on it.

Company culture often sets the stage for sunk cost mistakes. Some organizations punish failure by withholding bonuses, delaying promotions, or firing employees attached to failed projects. Also, managers are not trained in how to handle failure. They might become stuck on a project that is not fulfilling rather than raising concerns or stopping the project.

Company culture often sets the stage for sunk cost mistakes.

On the other hand, even if a project succeeds, employees might only receive a pat on the back or public acknowledgment. This creates an expectation that everything should turn out as planned, regardless of reality.

What organizational strengths protect against sunk cost fallacy?

- Promote a growth mindset where learning from failures is valued and celebrated. Have open discussions on what went wrong and how to improve. Lead by example by acknowledging the “win” of not escalating commitments.

- Teach employees and management to fail fast and fail smart. This means a hypothesis and realistic action plan implemented, executed, and measured with built-in decision points based on agreed-upon metrics that allow the project to continue or change course. Make sure that project successes and failures are not confused with a individual’s successes or failures.

- Push decision-making to the doers. They’re the ones closest to the effort, resources needed, and realistic timelines. If a higher-up champions the project (so there is an emotional attachment to its completion), build in “reality checks” constructed by team members on the ground.

- Follow the data. At go/no-go checkpoints, compare data-informed scenarios: continuing the project, stopping the project, and an alternative. Designate people to bring dissenting opinions and identify potential flaws and pitfalls. Make the decision based on pre-determined factors, like costs, benefits, and alignment with strategy.

Here’s how it should work.

Our client needed a new company portal. After determining guiding principles, MVP, and functional needs, they chose a vendor. But, well into the project, they conducted a review; they realized the selected vendor could not deliver the functionality they needed, and the partnership was fragile.

Rather than continuing with a subpar product, our client decided to cut their losses. It wasn’t an easy decision; a lot of time, money, and effort had already gone into the initiative. But they revisited their guiding principles and decided they could not be tied to a vendor that couldn’t meet their needs. Further, they realized that relying on a single vendor may not be the best approach.

We celebrate the courage and wisdom it took to make that decision. Hopefully, more organizations can align their strategy, culture, and practices to save themselves from hopeless initiatives.

-

Change Management for the Microsoft Power Platform

Key to developing business solutions and gaining insights from the Power Platform tool is user adoption, driven by solid change management.Empower Your Digital Transformation Using Our Change Management Methodology.

Organizations are under constant pressure to innovate, adapt, and streamline processes. Microsoft Power Platform has emerged as a key player, offering a suite of low-code/no-code tools like Power Apps, Power Automate, Power BI, and Power Virtual Agents that help businesses develop solutions, automate workflows, and gain actionable insights.

But, as always, the key to getting the benefits of any new tool is adoption. Adoption means solid change management.

Why do you need change management?

Change management is the structured approach to transitioning individuals, teams, and organizations from their current state to a desired future state. For digital transformation projects, it focuses on the human side of change, ensuring that users understand, embrace, and sustain new tools, processes, and technologies. Without proper change management, even the most powerful technology can face resistance or underutilization.

Implementing the Power Platform isn’t just about providing access to powerful tools; it’s about ensuring the workforce is prepared to use them.

What are the essentials of change management for Power Platform?

1. Stakeholder Engagement

Successful change starts with involving the right people early. For Power Platform projects, stakeholders include IT, business leaders, citizen developers, and end users. These groups must understand the vision and benefits of using the platform. By gaining their buy-in and addressing any concerns, you create advocates for the change.

2. Training and Support

Power Platform is designed to empower citizen developers. It has a user-friendly interface, but training is essential. Role-specific training ensures users feel confident in building apps, automating workflows, and generating reports. A structured support system, like a Center of Excellence (CoE), can provide ongoing guidance, best practices, and a community for peer learning.

3. Communication Strategy

When rolling out the Power Platform, you have to articulate the “why,” “what,” and “how.” Why is the organization adopting these tools? What’s in it for the users? How will employees’ work lives be different? Regular updates, success stories, and highlighting early wins can create momentum and foster excitement.

4. Governance and Security

Providing clear guidelines on app development, data security, and user permissions helps prevent shadow IT and ensures the platform is used in a controlled and compliant manner. Set up a governance framework to reduce risks and build trust in the new tools.

5. Phased Rollout and Feedback Loops

A phased rollout of Power Platform allows for better control and adjustment. Start small, with pilot groups or early adopters, and gather feedback. Use their insights to refine training materials, improve communication, and address challenges. This incremental approach makes the broader adoption smoother and more successful.

Why use the Power Platform Hub for change management?

For organizations with a Power Platform Center of Excellence (CoE), a centralized hub can be a game-changer. The **Power Platform Hub**, for instance, serves as a one-stop destination for learning, collaboration, and governance. It lets users connect with fellow citizen developers, access resources, and engage with community champions who can give them hands-on guidance.

By fostering community and continuous learning, the hub supports the long-term impact and sustainability of the Power Platform; it becomes part of the organization’s culture, rather than a one-time event.

How do you know you’ve done it right?

Finally, it’s essential to measure the impact of Power Platform adoption. Change management isn’t just about getting employees to use new tools; it’s about driving tangible business outcomes.

Metrics like app usage, automation adoption rates, time saved, and user satisfaction provide valuable insights into the success of the rollout. Continuously monitor these metrics so you can make adjustments and sustain the benefits you’ve gained.

Conclusion

The Power Platform offers tremendous potential. It can transform how organizations operate by empowering employees to build solutions that address their unique business needs. But technology alone can’t get the results you want—effective change management is critical to ensuring that users adopt and optimize the Power Platform. By engaging stakeholders, providing training, establishing governance, and supporting sustainability, organizations can harness the full power of tools like these and future-proof their business. And incorporating tools like the Power Platform Hub strengthens this approach, making it easier for users to learn, share, and innovate together.

As digital transformation continues to reshape industries, successful change management will be the key differentiator in building agile, adaptive, and high-performing organizations.

-

The Real Outcomes of Successful Change Management

Will Spring describes a 5-step approach to help an organization keep its eye on the real outcomes of its change management investment.Follow these steps to see beyond the project and focus on lasting outcomes.

Organizations are constantly implementing new systems and processes to stay competitive. However, sometimes people are too focused on technical aspects and not the ultimate impact and long-term outcomes.

During a recent meeting, this became very clear to me. We discussed our client’s implementation of a new time-tracking system and the importance of challenging organizations to think bigger.

Take the client’s perspective.

During a part of this meeting, we focused on identifying key behaviors we wanted to see from stakeholders as part of the implementation process. My group’s focus was the client’s maintenance staff; the behaviors we wanted to see were efficiency and professionalism.

As we talked, I found myself thinking from the client’s perspective. If I were a client, why would I care about the behavior of Joe in maintenance when all I want is a new time tracking system? It’s a straightforward request, right? Just get the system up and running, and we’re good to go.

Look beyond the finish line.

We talked about the fact that implementing a new system isn’t just about the technical rollout. It’s about understanding the bigger picture and aligning the change with broader organizational goals and outcomes.

At first glance, it might seem like our client’s objective is simply to streamline timekeeping and make payroll processing more efficient. But why do they want those things? Are they looking for insight into how employees are spending their time? Is it about eliminating manual processes to reduce errors and save costs? Or is there a larger goal? There is! Keep reading.

Use the power of “why.”

We explored what the client really hopes to achieve with the new system. One way to do this is a version of root cause analysis, or the “five whys.”

Client: We want a new time-tracking system.

Us: Why do you want that?

Client: To improve efficiency.

Us: Why is that good?

Client: It reduces the burden on staff?

Us: Why do you want to do that?

Client: So they can spend time focusing on customers.

Us: Why is that good?

Client: So customers are happy and loyal to our organization.

Us: And why do you want that?

Client: To sustain and grow our company.

By asking these questions, we discovered that the goal wasn’t just about tracking time, it was about creating a better customer experience.

Follow these steps.

How can we help organizations to think this way?

- Ask the right questions. Encourage clients to really explore the reasons behind the change by asking, “Why is this change important?” and “What long-term benefits are we aiming for?” Push them to go beyond the project milestones and make connections they might not have considered.

- Begin with the end in mind. Kick off the project by clearly outlining what you want to achieve. What are the ultimate goals? How does this change align with the organization’s mission and values? Help the project team keep their eye on the prize.

- Communicate the big picture. Everyone needs to understand the outcome you are aiming for and in what ways they are essential to reaching that vision. Build the right messaging and make that the foundation of all communications and training.

- Focus on behaviors. Change isn’t just about process or technology; it’s about how people engage with them. Identify the key behaviors that will drive the change and create strategies to encourage these behaviors. Then communicate, train, and reinforce those behaviors.

- Think beyond the immediate impact. Think past “go-live” or “Day One.” What activities and behaviors do you need from the project team and from stakeholders to reach and maintain your ultimate goal?

As change leaders, we must help clients see beyond the project and understand how these changes fit into their bigger vision. By connecting the dots from an operational change to a broader strategic objective, we can focus everyone’s energy on these impactful outcomes.

-

Your Project Got Past Go-live. Now the Fun Begins

People often think the “end” of system implementation projects is go-live, but it's not! Use our tips for post-go-live change management support.Tips for post-go-live change management support.

System implementation projects are difficult. They are tedious. They are stressful. And yes, they are costly. Often, we just want to get to the end. Many people think the “end” is go-live, but it is not. Everything you did to get to that imaginary finish line we call go-live just gets you to the starting line of the new way of working for your team. In other words, go-live is the start of the change.

Large-scale change initiatives do take a toll on everyone involved, so it’s understandable that we just want to be done. Many times, organizations begin reducing the project team to save on the remaining budget.

It’s common for the Change Management team to be the first ones asked to leave — immediately following go-live, if not before. After all, the training is done, and you have been “communicating” for months. Why keep the Change Management team?

If you don’t know the answer to this question, talk to projects that released their Change resources at or before go-live. You may get varying responses, but the gist will be, “Don’t release your Change Management support too soon!”

There are critical tasks that should be supported by your Change Management team AFTER go-live. Things like:

- Post-Go-live Communications

- Post-Go-live Readiness Assessments

- Lessons Learned

- Key Performance Indicators

- Continuous Education / Training

Remember: Don’t release your Change Management support too soon.

Post-Go-live Communications

Hypercare typically runs for a month after go-live. During this time, users are working in the new system. Occasionally, they might reach out for help. Your Change Management team can help to coordinate the onsite Hypercare resources, monitor project mailboxes for questions, and provide any on-going ad hoc communication requests. They can also help by creating weekly updates to keep the senior leaders engaged as the organization takes its first steps with the new ways of working.

Post-Go-live Readiness Assessments

The most critical goal for change management is employee readiness. To that end, we conduct readiness assessments, both pre- and post-go-live.

- The results of pre-go-live assessments help you understand what to change before you proceed to go-live to give you the best chance of success. They can be used as a final stage gate; a green light on readiness means you go live.

- The results of post-go-live assessments tell you how to correct course on your current launch, and how to conduct future releases or phases.

In either case, your Change Management team will be best suited to facilitate the readiness process.

Lessons Learned

Your Change Management team can pull together your core project team, key leaders, and select individuals from your stakeholder community, to discuss lessons learned throughout the project.

This is a critical activity. Not only will these lessons help you in future releases and phases of the same project, but these knowledge nuggets will help you and your organization during future initiatives. It’s the way you retain institutional wisdom, getting smarter and sharper with each project.

The most critical goal for change management is employee readiness.

Key Performance Indicators

It is likely that your Change Management team helped to identify the key performance indicators (KPIs) for your project. Facilitating KPI tracking is a good role for Change Management, while other core team members ensure the system is functioning properly and keep the business running.

Continuous Education / Training

Training is usually conducted a few weeks prior to go-live. Once all users have been trained, your Change Management team will support the trainers as users practice in the sandbox leading up to go-live.

- After go-live, someone must figure out how brand-new users will be trained. What are the courses (related to this new system) new employees should take? Who will function as trainers after the project has ended? What role will HR (Human Resources) play in helping to onboard new employees with this new technology? Your Change Management team can help to develop the approach for post-go-live training.

- The Change Management team should also identify and support remedial training. Post-go-live is when you really find out how the new systems, processes, and people are functioning together. If something is wrong, indicated by project KPIs, post-go-live assessments, or employee concerns, additional training might be the solution.

So, as you can see, keeping your Change Management team on board for some time AFTER go-live can be beneficial. What you need depends on your project, your organization’s capabilities, and the scope of the change. You might not need to retain your entire team, but having at least one solid Change Management resource on your team after you go live can make a significant difference in your results as your company begins its new chapter.

-

The 2024 Microsoft Outage and the Lessons Learned

The 2024 Microsoft outage is an unscheduled reminder to use (and keep sharp) best practices in technology change. Here are some practices to help prevent widespread tech issues.The 2024 Microsoft outage is an unscheduled reminder to use best practices in technology change.

The repercussions of the CrowdStrike update have us shook. The 2024 Microsoft outage is a timely reminder that rushed or mismanaged system changes can lead to chaos. How can you avoid the pitfalls of poorly planned technology changes?

Invite folks to the table.

First, consider the scope and implications of your change. Then ensure the right people are involved in planning, testing, and adoption. Identify and engage every group who might be affected by the change; solicit their input, identify impacts, and make sure you’re aligned.

- System Interdependencies: What other systems are involved with the system that is changing? Consider both upstream and downstream applications.

- Stakeholder Impact: How will this change affect the lives of employees, partners, and customers? How will they react? Ask questions, investigate thoroughly, and avoid making assumptions.

Consider the scope and implications of your change.

Test early, often, and thoroughly.

Experimenting and evaluating are crucial components of any change implementation. Test early, when it’s less painful to fix things. Test often, so you catch errors at each stage. Test thoroughly, so there are no surprises. Here are some essential testing strategies:

- Functionality Tests: Ensure the program/system is functioning as designed within the Sandbox environment.

- Platform Tests: Verify that the published program/system operates correctly in various live environments.

- Blind Individual Tests: Have individuals outside of the project team test the program/system to ensure usability and functionality from an unbiased perspective. Studies show that the closer you are to something, the less objective you are. Your brain automatically sees it the “right” way rather than the way it actually is.

- Stress Tests: Conduct stress tests to catch any defects early and minimize their impact on the organization and other stakeholders.

These protocols help identify and rectify defects early, ensuring a smooth and reliable implementation with minimal disruptions to your operations..

Timing is everything.

There is a long-running adage in the programming world – “Don’t deploy on Friday.” Some view it as a joke, others a jinx, but many consider it a must.

Risk management exists for a reason; no system is perfect, no team is perfect, so it’s prudent to plan accordingly. Not only do Friday deployments reduce the margin for error to fix an issue, but key stakeholders are often less available. This has implications for your team, but also your stakeholders, who might not see any communications or troubleshooting materials you share on a Saturday. Finding the right time to launch your change mitigates risk and improves adoption.

By incorporating these practices, organizations can better manage changes and prevent the type of widespread issues that resulted from the recent CrowdStrike update.

-

Public Sector Pro Tip: Use More Stories

Here are a few reasons government agencies should integrate storytelling into their change management approaches.How Government Agencies Use Storytelling in Change Management.

Change management is an essential function for any organization, but it’s especially important for federal government agencies. Change initiatives help drive the agency’s mission, which can impact millions of US citizens. Storytelling is fundamental to effective change management. Stories engage, inspire, and move people to action, making them a potent tool for leaders helping their agencies change and thrive.

Here are a few reasons government agencies should integrate storytelling into their change management approaches.

1. Stories work.

Humans are naturally drawn to stories. Stories are how we make sense of the world and our place within it. In the context of federal agencies, stories can transform abstract concepts into tangible examples that employees can understand and relate to. When leaders share stories of successful change, they provide a narrative that helps people envision the positive outcomes of the transformation.

2. Stories promote your change.

A compelling change narrative should be authentic, relatable, and aligned with the agency’s values and mission. It should illuminate the “why” behind the change, the vision for the future, and the role each employee plays. For instance, a story about how a new technology will improve citizen services can help employees see the importance of their contribution to the larger goal.

3. Stories combat resistance.

Stories are also powerful learning tools. They can be used to illustrate best practices, common pitfalls, and lessons learned from past changes. By sharing stories from within the agency or similar organizations, leaders provide a roadmap for navigating the complexities of change; this tamps down resistance and builds confidence in the change.

4. Stories engage employees.

Change can be daunting. But stories can create emotional connections that facts and figures alone cannot. They can motivate employees by describing the human impact of the change, such as how it improves the lives of the public or enhances the work environment for staff.

5. Stories drive commitment.

Inclusivity should be a cornerstone of stories in change management. Diverse perspectives help the narrative resonate with a broad audience and make all stakeholders feel heard. Inclusive stories foster a sense of belonging and commitment to both the change process and the agency.

The power of story in change management cannot be overstated. For federal government agencies, where change can be particularly complex and impactful, stories unite, guide, and inspire employees. As agencies continue to evolve and adapt to new challenges, the stories they tell will shape their path forward.

-

Top 5 Signs You’re Doing Change Management Wrong

If your organization is on a change journey and you’re feeling uneasy, look for these signs you might be doing change management wrong.Leading change management in your organization? These are signs you don’t want to see.

Any organization can go from Point A to Point B on a project, but if you want to get there in one piece and ready to reap the benefits, you need great change management. If your organization is on a change journey and you’re feeling uneasy, look for these signs you might be doing change management wrong.

1. People are telling different stories about what’s happening.

If there’s confusion surrounding the change, its progression, or the future state, it’s a clear indicator that something’s wrong. Clear and consistent communication is crucial at every stage of the change process to ensure that everyone understands what’s happening and why.

Make sure you have:

- A simple message framework that outlines why the change is happening, what the change is, how you’ll move forward, and what the result will be.

- Executives aligned on that framework, so they don’t need emails or PowerPoint decks to speak authentically on the change.

- A change network of key people embedded in stakeholder groups.

- Communication assets and channels to arm your change network as they spread the right information.

2. Employees are avoiding project activities.

Resistance often arises because employees simply fear what they don’t understand. They might worry about job security, lack of confidence in new skills or behaviors, or how their roles might change.

- First, be as transparent as possible. If you don’t tell people what’s happening, they will fill those gaps on their own.

- Second, allay those fears by building the right comparisons into your communications. Creating connections between your change and other experiences makes people feel it’s familiar, which turns off fear, makes the change feel valuable, and helps people remember it.

3. Employees are less happy.

A decline in employee morale and productivity is a big red flag that your change management approach is not hitting home with your staff. They might feel that they have no control over what’s happening, and they won’t be able to perform. Those in managerial positions might resist a change that takes away responsibilities or decisions.

Even a big, challenging project shouldn’t leave people down in the dumps. One cure for the slump is to create a sense of optimism for the future. That means two things: success and control.

- Engineer small wins early in the project. Look for ways to make stakeholders think “I was successful with that. I can do something like this again.”

- Then let them take the wheel for a bit. Involve stakeholders in decisions, mapping out the journey, and framing the new possibilities for their teams. Give them choices between solutions, locations, timeframes, etc. Having input into one’s future is a powerful boost. Adding choice, structure, and predictability makes a big difference.

4. Employees are saying it’s not right for their team.

If everything about your project just feels wrong to employees, or worse, directly conflicts with how employees work and succeed day to day, you’ll fail.

- First, seek to understand your organizational or team culture. If you haven’t already, put it into words. List the unwritten rules for success in your workplace – things like values, norms, and communication styles.

- Then, intentionally build them into the change management strategy and activities. If project communications and activities just feel right to people, you’ll foster acceptance and adoption.

5. You’re getting déjà vu.

Are you seeing or hearing about some of the same problems over and over throughout your project? Or are they similar to issues you faced during other projects? Maybe you’re not getting enough intelligence to act on. You need ways to capture and address feedback and lessons learned.

- Early in the project, assess your change readiness in key areas. That will give you a chance to get ahead of issues.

- During the project and after implementation, conduct pulse checks and gather stakeholder feedback through your change agent network.

- Document lessons learned from the project team and stakeholder groups at the end of the project. Then make sure you store, share, and socialize them. Better yet, build “change history check” into your organization’s methodology.

Change is hard…

An organization’s change journey can make everyone feel uneasy, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Look for the signs discussed in this post to avoid doing change management wrong. If (and more realistically, when) problems pop up, turn them into opportunities. See these valuable signs for what they are, correct course and get your change management right.

-

Will AI Improve Your Organization? It depends

As the AI landscape evolves, some organizations are simply running to keep up, with no clear destination. How do you know if you’re headed in the right direction? Here are some hints.Use your organizational values as a compass in an automated world.

Imagine walking into a workplace where decisions are made at the speed of light, tasks are completed with superhuman precision, and innovation is not just a buzzword but a daily reality.

This is the vision many organizations are chasing as they adopt artificial intelligence (AI). But as the AI landscape continues to evolve, some organizations are simply running to keep up, with no clear destination.

How do you know if you’re headed in the right direction? Our tip — check each milestone against your organizational values.

Why Values Matter in the Age of Automation

Without a strong set of values guiding AI, organizations find themselves in a maze of ethical difficulties and impersonal interactions.

For instance, what if an organization deployed AI chatbots for customer service without adequately addressing their limitations? This could frustrate customers and badly damage the brand.

Don’t automate processes without considering the implications and checking them against your values. Automation should enhance, not replace, the human touch. Every outcome should be aligned with the organization’s mission, vision, and values.

Without a strong set of values guiding AI, organizations find themselves in a maze of ethical difficulties and impersonal interactions.

The Role of Values in Decision-Making

Just because we can, does it mean we should? What guides our organizational decisions?

AI systems learn from historical data, which can contain biases. If the data are biased, the AI model might spread those biases. Imagine an AI-powered hiring tool that inadvertently discriminates against certain demographics due to biased historical hiring data. This could lead to unfair employment practices and even legal repercussions.

If, instead, the organization embeds its values into decision-making, it creates a culture of consistency and trust. Employees and other stakeholders understand that company actions are founded on those values.

Values and ethical rules should guide our decisions, not software features. Values ensure that as we delegate tasks to machines, we’re not also outsourcing our ethical responsibilities.

Just because we can, does it mean we should?

Protecting the Human Heart in a Digital World

As we embrace the incredible potential of advanced automation, let’s not forget the human heart beating at the core of our organizations. It’s the passion of the people, guided by clear and compassionate values, that will ensure technology enhances our work rather than defines it.

For instance, a hospital may have AI-driven diagnostic tools that are incredibly accurate, even revolutionary. But healthcare workers know that delivering a diagnosis without empathy will cause patients anxiety and distress. The most successful organizations will be those that harness the power of automation without discarding human insight.

Automation should enhance, not replace, the human touch.

So, let’s program our future with not only intelligence, but with wisdom and foresight. As our capabilities grow, so can our humanity.

Three Takeaways for Optimizing AI

Values are the compass. In a world steered by automation, clear organizational values provide direction and purpose, ensuring that every technological advancement serves the greater mission.

Ethics determine the heading. As automation becomes more prevalent, the temptation to prioritize efficiency over ethics can grow. Maintaining clear values helps resist this temptation and fosters a culture of integrity.

Advanced automation is a crew member, not the captain. While automation can greatly enhance efficiency and decision-making, it should not inhibit the passion and judgment of the people that make up the organization.

As the lines between human intuition and AI are blurring, clear organizational values have never been more crucial. As we sail into the uncharted waters of AI, these values are the stars by which we navigate, ensuring we don’t get distracted by shiny new software and lose sight of our humanity.

-

Working with a Consultant: Alignment and Expectation-setting

When working with a consultant, we recommend setting expectations and agreeing on the work to get the outcomes you want.Tips for success when collaborating with a consultant.

A sure way to guarantee failure on a project is misalignment. Setting expectations and agreeing on the work is critical to getting the outcomes you want from your consulting relationship.

Speak and listen.

Alignment begins at the beginning. Make sure your consultants understand what the problem is and how you want to them to help. Answer questions and give them access to the information or people they need to understand the situation. Ask your consultant questions about who they are, how they work, and what you can expect. And if they start speaking “Consultantese,” stop and ask them to clarify.

Agree on the work.

Once you’ve decided on the path forward, agree on the statement of work. Be sure it includes everything you want consultants to do to help solve your problem. The statement of work should describe the deliverables the consultants will create for you. Ask to see samples of those deliverables.

Ask your consultant questions about who they are, how they work, and what you can expect.

As you review those samples, ask yourself, “Will these deliverables help to solve this problem for my company?” If the answer is no, then speak up. Work with the consultant to customize the deliverables to fit you and your company. Once you are aligned, sign the statement of work and begin the engagement.

Sync your work styles.

Expectations are not just for the “what” but the “how.” So talk about working styles and boundaries. Do you prefer to have meetings in the mornings or afternoons? Are Fridays off-limits? Are you ok with working through lunch? If your consultant is flying in, is there a certain time you want them to arrive on Mondays…or leave on Thursdays or Fridays? Should consultants send meeting invites directly to you and your team, or go through an assistant? What communication channels do you prefer – email, phone, or a messaging platform like Teams? How should you share documents? Should business calls go to business numbers or are cell phones ok too? What are the “unwritten rules” of working with your company or team?

Kick it off.

Conduct a kick-off meeting the first week of the engagement. Invite the project sponsor, the project team, and any other key stakeholders. During this initial meeting, have your consultant explain to the team why they are there…what they plan to do and how they will work with the team.

Talk about working styles and boundaries.

Share the timeline that was included in the statement of work. Does it jive with the project’s timeline? Do you need to make adjustments? Agree on when deliverables will be submitted and how they’ll be submitted. How many days before a formal deliverable review should deliverables be sent? Who will sign off on deliverables? Who will act as the consultant’s main point of contact?

Communicate systematically.

Continued communication is the key to maintaining this alignment. Check in on a weekly basis. Set up status meetings. Decide who should facilitate those meetings and who should attend those meetings, and how they will be run. Agree on the format of the status report. What information will be most helpful to you as the project progresses? What are your deal breakers for project management? Any lessons learned from previous projects? Milestones, templates, and rules should guide your communications.

Avoid surprises.

As the project moves forward, keep your consultant abreast of any changes in scope, timing and/or budget. Last-minute changes aren’t good…but they are better than not communicating at all – that can really sink your effort.

Continued communication is key to maintaining alignment.

If something changes, sit down and speak with your consultant. Sometimes a fix can be as simple as creating a change order to reset expectations and get realigned.

What else should you talk about when starting and maintaining a great working relationship with your consultants? HINT: Anything that helps you to have a smooth working relationship and a successful project.