Change Management.

-

Build Your Team’s Resilience

How do you get top performance from your teams while supporting them through these crazy times? Brain science has the answer. Emerson CEO Trish Emerson explains how leaders can use hacks to build people’s strength and resilience.Hacking Human Biology to Improve Performance

According to the Harvard Business Review (1), employee productivity in most organizations dropped by at least three to six percent during the COVID-19 pandemic. Leaders have a particular challenge, balancing employee output with supporting them through today’s very real issues. But there are hacks we can use to help our people be more resilient, all based on our biology.

The Problem

It’s hard for our brains to process stress and think strategically at the same time. (2) When we see or hear something, our brains try to make sense out of it and determine a response. If we perceive a threat, our amygdala gets involved. You might know the amygdala from its biggest hit: Fight or Flight. If the threat seems strong, the amygdala might react quickly at the expense of the frontal lobes, which are trying to make sense of everything and compose a rational response.

Stress impacts our capacity to perform. Stress physically changes our brains. (3) It steeps our brains in hormones that change its physical structure: neuro-processors get shorter and the prefrontal cortex gets smaller.

These physical changes impact everything. Science writer Virginia Hughes elegantly explains this relationship in Nature. In Stress: the roots of resilience, (4) she writes that those with PTSD have an underactive prefrontal cortex and an overactive amygdala, and that resilience depends on the communication between the two.

But we are built to bounce forward.

Researchers took MRI’s of the brains of stressed students, and observed physical damage. Then, they measured those brains after one week of vacation, and found their neuro-processors and damaged dendrites had regrown. But here’s the interesting part: they did not end up just as they were before. The repairs suggest that the brain increases capacity to address future stress.

So our teams are under unusual stress, which diminishes performance, but they have the capacity to be resilient. How can we promote this resilience?

The Leaders’ Role

We can do two things to promote resilience: 1) give the team agency, and 2) give the experience meaning.

Agency matters.

Agency is the sense that person can impact an outcome. People with active control over their experience are resilient—they feel stronger and more resistant to challenges. Here are three ways to create agency.

- Engineer progress. It is imperative to give people simple tasks that show progress. Focus on a simple, observable activity that produces an outcome—not on the ultimate results themselves. It’s like the doctor pushing us to stand soon after surgery. She doesn’t say, “Heal!” she says, “Stand!” Because standing will get us walking, and walking will return us to full health.

For example, if we know that sales come from relationships, focus the team on contacting one client a day. That’s it. Then celebrate the completion of that step. It’s something they can control—it’s achievable and they can report success. Over time, the constancy of those moments will create results that matter. As Robert Louis Stevenson wrote, “Don’t judge each day by the harvest we reap but by the seeds that we plant.”

- Play the part. The physical and psychological are intertwined. Alison Wood Brooks, (5) at Harvard, studied reactions to certain types of fear, like stage fright or falling. She found that the sensation of fear and excitement are closely related. When she asked her subjects to say out loud, “I’m excited!” or “Get excited!” before a scary event, they reduced their anxiety.

Actors have known this trick for a long time. If we act happy—if our body language is open and we smile—we can actually produce that emotion. During COVID-19, a good number of us have been acting sad—withdrawing from friends, not dressing, and staying home. Small wonder depression has risen during COVID.

What can we do? We can model a bright mood and dress like we care. It might seem superficial, but the mirror neurons on our colleagues’ brains will encourage them to catch the positive emotion.

- Create fresh starts. It’s hard to move forward or express positive emotions in the face of daunting obstacles, like a global pandemic and lockdown. One way to clear those hurdles is a reset. Daniel Pink, author of When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing, (6) tells us we have a wellspring of opportunities for resets. Look at the calendar for the start of the next year, quarter, month, week, or even the next new day. Look for holidays, birthdays, new team members, anniversaries of shared success. And we can manufacture resets, too—this is one reason software development sprints work—a long project becomes a series of kick-offs and accomplishments.

As leaders, we can create agency to promote resilience. We can give people active roles in a change, including choices and options. We can also engineer events that promote the expression of positive emotions and the feelings that come with fresh starts.

Meaning matters.

How we interpret stimuli determines our responses. We act based on the stories we tell ourselves. For example:

Is this picture good or bad? It depends.

Is this picture good or bad? If you’re a dog person you might think this dog is playing. If you’re not, you might think the dog is vicious. We filter information through our own lens, and construct stories about the world.

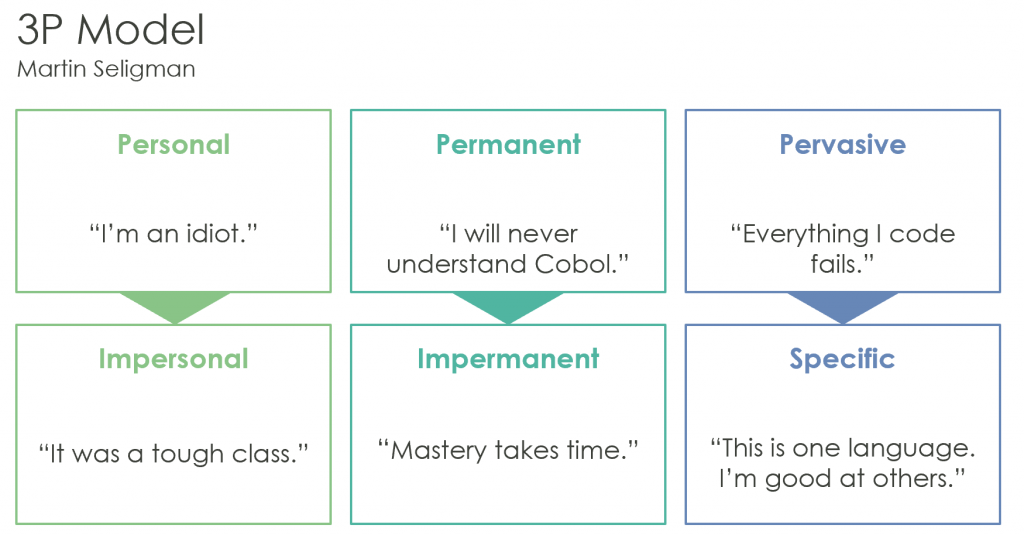

Martin Siegelman is the University of Pennsylvania psychologist who gave us the idea of learned helplessness. He describes this process of interpretation in his 3P model. (7) He says that, when we encounter an experience, we might define it as personal, , and pervasive. For example, let’s say we’re struggling with an assignment in a computer science course. The table below are the alternative interpretations, according to Siegelman’s model.

As we can see, a negative event seen through the three Ps is potentially harmful to a person’s self-image and ability to perform. But reframing the experience to show that it’s impersonal, impermanent and specific is compassionate and can help people bounce back.

As leaders, we provide the context. We don’t need to twist a bad experience into a good one—we can simply acknowledge it. Then, depending on the event, we decide whether to reframe it. Some bad things are so horrible, we should just affirm people’s feelings and be with them. But for your average, everyday failures: reframe it.

Take it out of that personal / permanent / pervasive space.

Retell the story as a bad experience with a finite context that doesn’t confer blame or foretell the future. Give the experience meaning.

Conclusion

In business, we can tend to focus on intellect and will. Old school, Type A winners flourish on vending machine food, florescent light, and four hours of sleep, right? To fix performance issues, we have told our employees (and ourselves) to power through. So it’s inconvenient to acknowledge that we, and our teams, are basically animals with a strong connection between what we experience, how our bodies respond, and how we create organizational results.

Today, we have the knowledge and tools to do something about it—to foster resilience and high performance. It’s a strategy not only for these tough times, but for sustained success.

References:

- https://hbr.org/2020/12/the-pandemic-is-widening-a-corporate-productivity-gap

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228115061_Stress-induced_changes_in_human_decision-making_are_reversible

- Recognizing resilience: Learning from the effects of stress on the brain – ScienceDirect

- Stress: The roots of resilience : Nature News & Comment

- Get Excited: Reappraising Pre-Performance Anxiety as Excitement – Article – Faculty & Research – Harvard Business School (hbs.edu)

- When: The Scientific Secrets of Perfect Timing

- Martin Siegelman’s Positive Psychology

-

President Biden Gets an A in FCS

When Emerson helps organizations manage change, we make it feel Familiar, Controlled, and Successful (FCS). Here’s how President Biden used FCS in his COVID-19 speech.Co-authored by Mary Stewart

How the President’s Primetime Address Used Brain Science to Unite the Country

On Thursday, March 11, 2021, much of the country tuned in to President Biden’s first primetime address to the nation. His challenge was clear: unite the country to act according to his plan, and bring on the end of the pandemic. The audience, no doubt, was diverse in its attitudes toward Biden and readiness to follow his lead. How would he persuade resistant Americans to do the right thing?

We are in the business of aligning organizations around a change and creating positive momentum. So we feel you, Joe. And we think you did the right thing. You used the principles of brain science to your advantage, just like we do.

When we help our clients manage a change, we make it feel Familiar, Controlled, and Successful (FCS). Here’s how the President used FCS in his speech.

Familiar

Our brains see new things as dangerous. Any change generates fear, which causes resistance. Creating connections between your change and other experiences makes people feel it is familiar, which turns off fear.

One way to do this is to compare your initiative to something people know and remember as being successful.

“I’m using every power I have as the president of the United States to put us on a war footing to get the job done. Sounds like hyperbole, but I mean it, a war footing. …It’s truly a national effort, just like we saw during World War II.”

”The development, manufacturing, and distribution of vaccines in record time is a true miracle of science. It’s one of the most extraordinary achievements any country has ever accomplished. And we all just saw the Perseverance Rover land on Mars. Stunning images of our dreams that are now reality.”

See what he did there? He didn’t just talk about the Trump administration’s initiative, or even invoke other pandemics, like H1N1 or Ebola. He used winning WWII and landing on Mars. He tapped into familiar, positive feelings and attached those feelings to the current initiative.

Controlled

We don’t like to move forward in the dark. Our brains crave control. Adding choice, structure, and predictability makes the change feel controlled, so people feel less anxious, more engaged, and feel free to take action.

One way to create feelings of control is to give people information, so they aren’t surprised.

“I met a small business owner, a woman. I asked her, I said, ‘What do you need most?’ …and she said, ‘I just want the truth. The truth. Just tell me the truth.’”

Another way to create feelings of control is to talk about milestones. Tell people what is going to happen, and when.

“I said I intended to get 100 million shots in people’s arms in my first 100 days in office. Tonight, I can say … we’re actually on track to reach this goal of 100 million shots in arms on my 60th day in office… All adult Americans will be eligible to get a vaccine no later than May 1.”

A third way is to give people something to do, so they feel like they have a part in the change.

“But I need you, the American people. I need you. I need every American to do their part. And that’s not hyperbole. I need you. I need you to get vaccinated when it’s your turn and when you can find an opportunity.”

Finally people who have clear instructions and tools feel in control because they know exactly what to do.

“…in May, we will launch…new tools to make it easier for you to find…where to get the shot, including a new website… No more searching day and night for an appointment for you and your loved ones.”

He said he’d give accurate information, previewed the road ahead, told people how they can take action, and promised them support to do so. All of those messages grant control to the listener.

Successful

Winning releases dopamine—the feel-good neurotransmitter. Sharing successes releases oxytocin—the connection hormone.

One way to create a feeling of success is to create and highlight small wins.

“You can drive up to a stadium or a large parking lot, get your shot, and never leave your car, and drive home in less than an hour.”

“Millions and millions of grandparents who went months without being able to hug their grandkids can now do so.”

Another way to foster success is to celebrate collective wins.

“When I took office, only 8% of those over the age of 65 had gotten their first vaccination. Today that number is 65%. Just 14% of Americans over the age of 75 …had gotten their first shot. Today, that number is well over 70%.”

“…if we do this together, by July the 4, there’s a good chance you, your families and friends, will be able to get together in your backyard or in your neighborhood and have a cookout or a barbecue and celebrate Independence Day.”

The President talked in vivid terms about success—individual success through quick shots and warm hugs, and collective success through high vaccination numbers, culminating in a national day of celebration.

Mr. President, we’re big fans, both of your pandemic plans and the way you convey them. Brain science to message and epidemiology to protect—that’s a winning team.

-

Three Ways to Use Agile Principles in Your Learning Program

Agile, as you might get from its name, is all about speed and flexibility. Here are a few ways to use Agile principles in learning programs.Agile principles can improve your training.

Agile is not just a software development methodology, but a mindset. One that can transform any kind of work, including learning program development.

What is Agile? Well, what it’s not is “waterfall”—the traditional development approach rooted in the industrial economy. Waterfall projects plan everything at once, then move on to design everything at once, then develop, and so on. Some of the benefits of a waterfall approach are consistency and accuracy—the team has a set of standards and it takes great pains to maintain them, across the initiative. That’s good, but it can take a very long time. And, by the time the end user sees anything useful, they have lost months (or years!) of benefit, and the landscape has probably changed.

Agile, as you might get from its name, is all about speed and flexibility. It reserves the right to be smarter today than yesterday. It’s about failing fast, adjusting course, and trying again. It’s about getting better and better, while effecting real-world change.

Here are a few ways to use Agile principles in learning programs.

Size. Here we’re talking about size of scope, size of teams, and size of the “batches” of work. Often, our teams are responsible for an entire curriculum. Subject matter and technical experts are available to the entire team. Once an instructional designer completes design of one module, they move on to the next one. When design is done, they start developing courses. The entire curriculum reaches each milestone together.

Instead, try micro. Build a team of one instructional designer, one SME, and one technical expert. Focus them on one course, to deliver one tight set of learning objectives to one set of learners. And then let them run; Agile teams call it a sprint. They should design, develop, pilot, and launch the training as fast as they can.

Worried your courses will be “all over the place?” First of all, they might, and that’s ok. Second, all consistency is not lost. As you gather feedback on course drafts and tests, craft a prototype module. This will be your gold standard – all great, client-vetted and universal design ideas go here.

Agile will deliver skills to your learners, fast. And the team will learn a lot; they aggregate lessons learned so all can benefit in the next sprint.

Focus. Learning team members often serve many masters: learning executives, business function leaders, technical team leads, project sponsors… Each entity wants oversight, to ensure consistent quality, style, format, and learner experience. Reviews ripple through the curriculum as it’s being designed and developed, requiring revisions and new standards. Subject matter experts might have to swallow changes that have nothing to do with their learners, but serve the program as a whole or please a particular executive.

Agile is all about the customer, and no one else. One of its lessons is “Be willing to disappoint.” That is, disappoint anyone but the customer. Using an Agile mindset, the learner is king. The SME represents the learner on the micro-team for the course. So if the SME believes a piece of content, a delivery method, or a particular style works for the learners of the course, you use it.

To sharpen your focus, create a “learner persona.”

Work with your SME to build a profile of the learner for this course. The learner’s responsibilities, location, technical acumen, etc. help you choose the right stories, metaphors, interactions, and delivery modalities.

And Agile would say let the learner tweak your product. So if you get quickly to a pilot test and then a launch of your course, let learners into the process. Ask them how to make it better; go beyond the “smile sheet” and let them be designers for a day. Then build their best ideas into the next version of your course and share it with the other teams, so they can benefit as they sprint.

Mindset. Does this all sound messy? It is. That’s why everyone involved must understand and adopt the Agile mindset if this is going to work.

It’s easy to frame Agile in a positive light. Chaos breeds creativity. Get comfortable with uncertainty. It’s an opportunity, not an obstacle.

But we have to accept that it’s a big change. Agile requires people to give up traditional control, watch as things fail and get better, tolerate inconsistency, and be part of a process that feels chaotic at times. How can you get everyone on board with Agile?

Here’s where we bring out our change management tools. Once you have the main decision-makers on board with this shift, make it familiar, controlled, and successful.

- Our brains see anything new as dangerous. To dampen fear, make this change feel familiar. Compare the new approach to other innovations that brought great things to your organization. Don’t dwell on the old learning development approach; frame the new Agile learning approach as another big success story—whatever success story resonates with them. That makes this change feel familiar and safe.

- People crave predictability and control. So give them something solid to grab on to. Roll out the shift to Agile using a timeline, and let them know what’s happening as you hit each milestone. And give people choices whenever possible. For example, you might ask for volunteers to try the Agile approach first. Any “early adopters” in your group will make the next steps feel doable for the rest.

- Winning feels good. So engineer success into the transition. Call out and celebrate your first Agile course achievements. And remember to reward the new mindset—we embrace failing fast, right? So, when you find problems in the first pilots or conducts, congratulate those teams for their boldness, courage, and valuable lessons learned.

Remember: Familiar, Controlled, Successful

Agile is a big change, with big benefits. Our software brethren have gone there, but why should they have all the fun? Learning teams who use Agile principles can deliver big benefits, fast.

-

Familiar, Controlled, and Successful

At Emerson, we like to take scientific findings and use them to help you get the business outcomes you want.There is a lot of research on the brain and behavior. Science can tell us why we feel and act the way we do. At Emerson, we like to take scientific findings and use them to help you get the business outcomes you want. There are three principles, based in science, which can help you make any organizational change or learning program better. Science tells us that if we want to implement something new in an organization, we should make it feel Familiar, Controlled, and Successful.

The first principle is Familiar.

Our brains see anything new as a threat. We feel fear. Familiarity can make a new thing feel safe and valuable. Familiarity is created by comparing the new thing to your past experiences. Compare the change to something good. Compare the change to something bad. Use what they already know. And, of course, we know stories are powerful. So you can use a story as the vehicle for each of these. I’ve used story telling on many of my projects. Typically, I find executives or well-respected managers to share stories that help make the change to feel familiar. Also, use repetition. Perhaps the information is new to people when you start the project, but if you keep repeating it over and over, it becomes familiar. I do this by having multiple resources sharing their stories.

The second principle is Controlled.

Our brains don’t like uncertainty and they don’t like feeling vulnerable. Giving people predictability and control lowers anxiety and unleashes people’s potential to plan and organize. Control is created by giving a change predictability and structure, and by giving people choices. Share a schedule or project roadmap to help those impacted by the change to understand when things are happening. This helps them to schedule the rest of life which gives them some control during the change. Also, Frequently Asked Questions provide stakeholders with additional information which helps them to feel control.

The third principle is Successful.

Brain research tells us exactly why winning feels good. And why winning together feels even better. A feeling of success is created by engineering small wins and celebrating milestones. One way to make someone feel successful doing something new is by breaking that new thing into small, simple tasks. Another way to make people feel successful is by making the new thing doable. Also, be sure to make your change measurable. Being able to measure it helps to show when goals are being achieved. Once those goals are achieved or those milestones are met, use rewards to encourage people to continue moving forward with the change. In past projects, I’ve set it up so that teams who are showing progress, get recognized by the company. This encourages them to continue moving forward and it helps the rest of the organization see how things should be done based on the new way of doing business.

Creating connections between your change and other experiences makes people feel it’s familiar, which turns off fear, makes the change feel valuable, and helps people remember it. Adding choice, structure, and predictability makes the change feel controlled, so people feel less anxious, more engaged, and get to use their brains’ executive functions. Engineering small wins; measuring; providing feedback and rewards; and celebrating make people feel successful, activating the feel-good chemicals in their brains. Use the simple strategies outlined here to make your change feel Familiar, Controlled, and Successful. In doing so, the change will be more quickly adapted in your organization.

-

Six Questions to Ask Before Hiring a Change Consultant

Some firms dazzle you with strategy and slick slides then head for the door. Don't let them leave you hanging -- ask these questions before you hire a change consultant.Don’t Let Your Consultants Leave You Hanging

We call them “deck and dash” firms—consultants who dazzle you with strategy, conceptual models, and slick slides…then wish you luck and head for the door. Now what?

Maybe that’s what you want, but at least be prepared. Make sure that they leave you in a place where you can get the benefits of your investment.

Before signing the contract, here are the questions you should ask:

- What will the business outcomes be? How will your work translate to benefits for us, specifically? It’s important to hear stories about their other clients, but the focus should be on your business. How does the work connect to your strategies and integrate with other initiatives in your organization?

- What has your team learned from similar implementations? Implementation informs strategy and design. Even if you are paying them to build deliverables and then hand them off to you to implement, you need consultants who regularly roll up their sleeves and help their clients launch. Consultants learn and sharpen from that experience.

- To what degree will you involve the business leaders impacted by this change? How? Many consultants like to touch base a few times to gather information, then go away and create — leading to a grand reveal of the solution. That’s fun and dramatic, to be sure, but it’s wrong. You need consultants who work with key members of your business, to ensure the solution is right for you, create momentum, and help the business plan for launch.

- What will the deliverables look like? Will they include implementation plans, timelines, and estimates? Ask to see samples from similar projects. Imagine being left with that deliverable. Could you use it? Would your business know how to get the benefits you expect?

- What does your last day look like? How will you transition your work to us? What you’re looking for here is their involvement in implementing the solution and your readiness to take it forward.

- What if we have questions after you finish the engagement? You need consultants who are invested in your success. If your people are sincerely confused or unprepared to use the deliverables the consultants built, then their work isn’t done. Make sure they commit to an ongoing advisory relationship to support what they delivered for you.

Paying for ideas, plans, and strategies might be right for your business. Just make sure you have a clear picture of your life after the consultants are gone.

Here’s how Emerson addresses the six questions:

- We helped a major university’s IT department focus on the outcomes they needed. Click here to read more.

- We helped a large U.S. government agency launch their HR strategy. Click here to read more.

- We worked with the largest hospital system in Missouri on a custom approach. Click here to read more.

- We built solid implementation plans for one of the best-known retail brands in the world. Click here to read more.

- We fully transitioned our work and expertise to a large pharmaceutical company. Click here to read more.

- We continued to support a business technology corporation with ongoing advice. Click here to read more.

-

Maintain Your Organization’s Work Style During Big Change

Transformation is stressful enough. Don’t make things harder by losing what works. Focus on these three areas to stay true to your organization’s work style.Work style is how things get done. It’s the day-to-day manifestation of your organization’s culture — the unspoken way we work and deliver projects. It’s framed by purpose and guided by values.

During times of intense change, it’s important to be aware of your organization’s work style, and to honor it. Transformation projects are stressful enough to knock even the strongest of us off-course. The best way to help your organization is to stay true to what works for you.

There are three key areas of focus.

Communication. How much communication does your organization need? What kinds of communication work for you? The channels might be formal, informal or a combination. Every organization is different. For example, if your teams are highly focused on running an operation, or they are spread out geographically, you might need dedicated, in-person events like town halls to reach them. Who are credible messengers to spread the word, — managers or respected peers? It’s critical to know what it takes to get employees to focus their attention.

Consensus Requirements. Does your organization run on consensus? The answer drives the speed of decision-making. Whose opinion matters? If all the key people need to buy in, build in time to gain that consensus. Identify which stakeholders have to bless each decision, follow a process, and make sure the teams know their voices have been heard. Depending on the topic, you might need less consensus. Take advantage of that – push work to the lowest-level teams that can make the decision.

Relationships vs. Structure. To what extent does work get done through deep relationships vs. systems and process? If relationships are important, plan for that. Create a framework that fosters relationships. For example, create robust onboarding, recognition methods, and celebration rituals. Relationship-based cultures will resist too much structure if it’s visible. If your teams are more systems-oriented, lean on those processes. But be careful – it’s easy to ignore a well-oiled machine. Make sure you review processes — at least annually — to ensure they help employees to their best work. Identify and close any gaps.

Clarifying your organization’s best working styles helps leadership strike the right balance between empowerment and accountability. And it makes any big transformation so much easier.

So, what’s your style?

-

From the Trails to the Office

After 25-plus years of consulting and 100 endurance races, I’ve noticed lots of parallels. Here are a few.9 Lessons Learned From 25 Years of Consulting and 100 Long Distances Races

After 25-plus years of consulting and 100 endurance races of half marathon, marathon and ultra-marathon distances, I’ve noticed lots of parallels. I’ve learned many lessons during my races that apply to my work as a consultant. Here are a few.

Lesson 1: Be thankful you’re able to lace up and go. Not everyone is capable of going for a long run. Some can’t make it due to their age. Some have health problems. If you can lace up and toe the line, you’re lucky.

Try to think that way about work. Sometimes it’s hard to jump out of bed and sprint to work with a smile on your face. But recognize that there are people who would give anything to have your job. Understand that you are blessed. Be thankful for the opportunity and make the most of it.

Lesson 2: You have to show up in order to finish. Lots of people talk about doing marathons and ultra-marathons. Not a lot of people show up on race day. In order to cross the finish line you have to first cross the start line.

It’s just as true in business. It’s critical to “show up” each day. You can’t succeed if you only bring your A Game occasionally. You have to bring it every day, for the duration of the engagement. You have to show up in order to get your project over the finish line.

Lesson 3: Drink before you’re thirsty. One of the keys to finishing long distance runs is hydration. Drink early and often. Your body will appreciate it and you’ll be able to go the distance.

As a consultant, it is important to stay abreast of the latest trends, research, methods, and technologies. Continuous learning is vital to serving your clients or supporting your business. Read. Attend lectures. Participate in professional conferences. Take online courses. Seek certifications. Don’t wait until you need to know something to begin your search—stay on top of the latest information in your field. In other words, “drink before you’re thirsty.

Lesson 4: Never pass an aid station without refueling. Sometimes, on the trail, runners feel like they are falling behind so they bypass an aid station to make up time. Inevitably, this comes back to bite them. In your race prep, you develop a plan. In that plan, you’ve outlined all the things you MUST do in order to be successful. If it is a good plan, stick with it. That includes refueling at the aid stations.

On your project, spend enough time planning the work. Understand where all the “aid stations” are. We often refer to them as milestones. Be smart about how and when you’ll get there. Be prepared to pause, take stock, and celebrate this small victory. Let your team know how well they’ve done to get to this point. Remind them where the next milestone is and what it will take to get there. You and your team will benefit from taking these pauses to refuel.

Lesson 5: On the tough parts, keep your eyes on the trail. When it’s safe, look up and enjoy the view. There are lots of obstacles along the trail. It’s easy to lose your concentration. It’s easy to stumble and fall. You have to maintain your focus to do well.

The same is true at work. Things come up. Obstacles appear. Keep your eyes on the “trail” as you move toward your milestones. Some parts of the project will be trickier than others. Use extreme focus on those parts. But, when you can, look up and take in the big picture. Celebrate how far you’ve come. Try to enjoy the journey.

Lesson 6: When you’re feeling good, encourage other racers. You’ll need for them to return the favor when you’re not. As you run past your fellow racers, offer them a word of encouragement. It’s amazing how your quick gesture helps push them along.

The same holds true with your work colleagues. Look for opportunities to stop and offer them a pat on the back, a kind word, or a listening ear. There will be days when you’ll need for them to return the favor.

Lesson 7: If someone goes down, stop and help them. On the trail, things happen—pulled muscles…twisted ankles…heat exhaustion…cramps…slips, trips, and falls. When you come across someone in trouble, you help them. You get them on their feet or you offer them water or you go for help. You don’t run past them.

In business, people go down as well. It is often obvious when someone is struggling. You can see that they’re not going to make a deadline or won’t deliver the best deliverable. Help them. Can you act as a sounding board? Stay after work to lend a hand? Give up your lunch hour to listen to your colleague practice a presentation? Figure out a way to help. Your colleagues will appreciate it and the team will benefit.

Lesson 8: Run when you can. Walk when you have to. Just get to the finish line. Finishing is what matters—not how fast. Many runners get stuck focusing on their time. They want to go fast. They want to set a personal record. And some push so hard they end up dropping from the race (because of injury, exhaustion, mental fatigue, etc.). Sometimes it’s better to slow down. Slowing down can help a runner get to the finish line.

In business, you’ve probably heard the saying, “Go slow to go fast.” This is the same concept. Sometimes there is benefit to taking a step back—revisiting the work plan and focusing attention in another area for a moment in order to ensure you get to the finish line. Keep your overall goal in mind. What is it you’re trying to accomplish? What problem are you trying to solve? I’ll bet it has nothing to do with how fast you finish. So, slow down. Get it right. Deliver a great solution. If your company or client tries to push you to finish faster, remind them why you’re there. Remind them of the benefits of success and the cost of failure. Let them know you want to get it right. Tell them, “sometimes you have to go slow to go fast.” Changing those behaviors, implementing that new technology, or whatever your project has been tasked with will eventually help your client go faster.

Just keep running.

Lesson 9: An endurance run isn’t the most difficult thing you’ll ever experience. When you feel like quitting, keep that in mind. Don’t get me wrong, some runs are very difficult. Running 31 miles through the mountains, in the rain, can be a challenge. Climbing thousands of feet in the heat, or running hills over and over again along a 26.2 mile course can be debilitating. You’ll want to quit. When these thoughts enter your mind, remember, this isn’t as hard as life gets. There are many things harder than running in the mountains. I won’t list them here; I’m sure you know what they are. I’m sure you’ve experienced some of them. When you think about those trials, you realize you have it pretty easy to be spending the day in the mountains, breathing good air, getting some exercise, and enjoying the companionship of like-minded people.

We all have tough days at work. Tough months… Tough clients… Think back to all those “tough” experiences. You survived them all. Keep plugging away. Recognize those bad days aren’t so bad; you can handle them. Just keep running.

Endurance running and consulting: same thing, different wardrobe. Who knew?

-

Virtual Onboarding

What we know about brain science can give your new employees a great transition to your virtual team.Make it familiar, controlled, and successful.

How do you onboard employees virtually? How do you get them engaged and performing through a screen? Most of us are acquainted with the basic mechanics of virtual onboarding:

- Welcome the new hire with something tangible like a plant, gift basket, or company-branded gear.

- Keep each virtual onboarding session short and interactive.

- Use strong presenters.

- Expand the elapsed time for onboarding from one or two days to as many as 30 days.

- Issue surveys to gauge engagement and solicit feedback for improvement.

But we think good virtual onboarding has to go deeper. When you’re onboarding employees, you’re asking them to change their behaviors—do this, in this way, to this standard. You are also hoping to reinforce their positive feelings about the organization, so they feel welcome and they are part of something great.

Science tells us that if we want behavior change to work, we should make it feel familiar, controlled, and successful.

Familiar

Our brains see new things as dangerous, so change – like a new job – can create feelings of resistance. But familiarity, as mentioned in other posts, feels “safe.” You can activate those feelings of safety in your onboarding program.

Determine what makes most new employees feel great about the employer—for example, the culture, the brand, the physical environment, the great people, and the proper supports and resources. Highlight those familiar “feel good” elements in your welcome video and guest speakers. The more you remind them of what they already know and like, the better.

Use video tools that are familiar to most participants. We all know Zoom. Many of us will not be familiar with GoToMeeting or TeamViewer. Make the login to the virtual onboarding easy. First impressions matter.

Include live speakers or filmed testimonials from people who look and sound more like your new employees. If your new hires are in their 20’s and mainly Black or Brown women, they won’t connect as well to, let’s say, middle-aged White men.

Repeat certain onboarding activities throughout the program; for example, use weekly check-ins with their boss and a peer coach. Over time, these events will start to feel familiar.

Controlled

Humans love to feel in control. Giving new hires the feeling of control reduces anxiety and frees their brains for learning and executive functioning. You can do this by building in structure, predictability, and choice.

Develop an onboarding timeline and share it repeatedly when meeting with the new hires. For example, if a group of new hires connects every week, show them the timeline with a “you are here” marker.

Provide new hires with the right tools: laptop, easy connectivity, digital onboarding tools, and job aids. How about a new hire portal or MS Team Site to house all this information? Include FAQs and key contact information they can have at their fingertips.

Give them some choices up front: Surface or MacAir? Flextime vs. standard business hours?

Build some flexibility into their onboarding tasks so they can exert some personal control over their schedules and not feel like their new employer is programming every minute of the day.

Successful

Winning releases dopamine, the brain’s feel-good chemical. And sharing success promotes oxytocin, the connection hormone. You can build success into your onboarding program.

Small and simple successes might be things like signing up for health benefits or getting their parking pass activated. Highlight each successful step. Consider gamification to track these successes, with a nominal reward or recognition at the end.

Handling some of their new job activities, with support of their new manager and peers, will also make them feel successful. Keep things small and simple in the beginning, so you are sure they will complete them correctly. (Failing at one of these tasks will produce the opposite effect!) Have managers give new employees coaching and feedback along the way. You could even build completion and sign-off into your gamification approach.

New hires feel more successful when they feel they are becoming part of the team. Interpersonal and social successes count too! Can’t gather at the local sports bar? How about a virtual happy hour or beer bash? Schedule some virtual team lunches or coffee breaks—the company could pay to have the meal or coffee delivered to the new hire.

The last word…

Create your company’s onboarding experience to promote feelings of familiarity. New hires will feel they’re more in control of their transition when you include choice, structure, and predictability. And they’ll feel more successful if you provoke the feel-good chemicals in their brains through small wins, feedback and rewards, and orchestrated virtual events that make them feel like they belong. It’s a different world now, but people are still the same. What we know about brain science can give your new employees a great transition to your team.

-

Tough Times Need a Tough Team

Faced with unprecedented challenges, your leadership team needs to get aligned and then sound aligned.Imagine this: your senior managers are hosting virtual meetings. In each one of them, someone asks a question. “What are we doing in response to the pandemic?”

- Manager 1: “We are doing everything we can to keep all of us safe.”

- Manager 2: “I know we all hate these Zoom meetings, but we will be back in the office as soon as possible.”

- Manager 3: “You were sent an email on June 14, outlining our response to the pandemic. I suggest you read that.”

- Manager 4: “What are you concerned about? Let’s talk about what I can do to help.”

Which is the right answer? All of them, and none of them.

None of the answers is wrong. But they are all wrong because they are so different.

People have a fundamental need to feel safe in order to function. Control and predictability create feelings of safety. Four different vague or evasive answers create just the opposite. The costs of this kind of uncertainty: resistance, lost productivity, and an organization even less focused on its business goals.

Faced with unprecedented challenges, your leadership team needs to get aligned and then sound aligned. That’s a tight team.

We have tightened up many executive teams. We don’t tell them what their goals and message should be; we facilitate. Here is the essence of our process:

- Gather your team and ask them four questions.

-

- What’s the challenge we’re faced with?

- What’s the solution to the challenge?

- What’s the approach we’ll take to execute the solution?

- What’s the result we want?

- For each question, brainstorm a one-word hint: start broad, then narrow down to the top two to three words, and then down to the final one.

- Once the four words are selected, generate facts and examples to use when you deliver the message. Each of the four words needs its own supporting details. Now you have a message frame.

- Bring it all together in a 30-second story – the four words, buttressed by facts or examples.

- Practice telling the story. As you practice, customize it for who you are and whomever you’re addressing. That is, use different examples for a Marketing employee vs. an IT employee. Each executive’s story will be slightly different, based on their communication style, area of expertise, position, and audience.

- Practice it a few more times, imagining different scenarios.

- Use the message frame as the foundation of all communications on this subject.

Let’s try our scenario again. Four Zoom meetings. Four employees with questions. Four responses from leaders.

“What are we doing in response to the pandemic?”

Feel that? It’s peace of mind.

-

Scaling Your Workforce in Tough Times

If you need to scale quickly, we have some ideas for you to consider.We all know the bad news. The US economy lost 20.5 million jobs in April 2020, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics—by far the most sudden and largest decline since the government began tracking the data in 1939. The unemployment rate soared to 14.7% in April, its highest level since the BLS started recording the monthly rate in 1948. The last time American joblessness was that severe was the Great Depression.

But it’s not all bad news. Certain businesses associated with logistics and supply of critical goods are actually hiring…like crazy. Instacart is hiring 300,000 contract workers. Amazon is bringing on 175,000 new workers for its fulfillment centers and delivery network. We see additions of 50,000 each for CVS Health, Dollar General, and Walmart. Lowe’s is hiring 30,000 employees. FedEx is hiring. Ace Hardware is hiring.

A company like Amazon is used to scaling up for seasonal hiring but many businesses are not. Hiring thousands so quickly taxes the organization’s entire talent management system.

At Emerson, we think of talent management holistically; it supports the organization’s culture and helps achieve desired business outcomes.

When you need to scale quickly, here are some ideas to consider:

Talent Acquisition

Standard career fairs and job postings won’t work right now. What are the best ways to acquire talent? How can you quickly identify the best when supply exceeds demand due to high unemployment?

- Tap into communities like church groups, food banks, university campus online boards.

- Work with other companies that have laid off or furloughed workers.

- Apply AI technology to filter best applicants.

- While it may be tempting, don’t hire the first warm bodies. Maintain your recruiting rigor with a focus on the critical skills for the job as well as cultural fit. In some markets and industries, it’s a buyer’s market, so leverage it and don’t settle.

Onboarding

Measured, multi-week onboarding doesn’t cut it when hiring thousands at one time. How can you streamline the process?

Use a “speed dating” model. Allow groups of applicants for similar jobs to familiarize themselves with the end-to-end process in a few hours by moving quickly through the main steps or stations. Then, assign a given cohort to specific coaches for more detailed on-the-job training.

- Show short videos rather than live demos or blend videos with live learning. Note that videos don’t have to be professionally done to convey key points. Think TikTok, not Ken Burns. Use a tripod and your iPhone.

- Update your critical job aids. Simplify them to highlight the common, critical, and catastrophic–the “must-knows and dos” for the job. Think about how employees will use the job aids. Should they be laminated or posted? Should they only be online? Ensure they are multi-lingual if needed.

- Make it easy to spot coaches or team leads through clothing, like a colored cap or vest or a large badge. Post visible “Ask Me” signs on the tops of the coaches’ workspaces.

- Appoint a buddy to each new hire for a quick-and-dirty mentoring program.

Engagement and Retention

Turnover is costly. For workers earning $30,000 or less, the typical cost of turnover is 16% of annual salary, or $4,800. For workers earning less than $50,000 annually, average cost of replacement is 20% of annual salary, or $10,000. Five to ten thoursand for each entry level job? Multiply that by a thousand and you can see how turnover can hurt.

Unemployment is high so getting a replacement worker is easy, right? No! Every turnover requires replacement costs like recruiting, physical or drug testing, background verification, and training.

Source: https://busybusy.com/blog/reduce-employee-turnover-cost/

Putting a little effort into retaining those you hire will save you a lot of money.

- Make your work environment positive, comfortable, and safe!

- Focus on respect for employees. Provide supervisors with tangible examples of what “showing respect” looks like.

- Offer appreciation with unexpected small perks like periodic snacks–maybe a weekly delivery of fresh fruit or some other food your employees would enjoy.

- Recognize employees during staff meetings. Make it more personal; for example, ask leaders to send handwritten notes to employees’ homes.

Development and Performance Management

Yeah, we know what you’re thinking: hire now and worry about development later. But it’s never too early to think about how you’re going to evaluate, develop, and retain that new hire. You’ve just placed someone in an entry level job; what are the criteria to determine she’s ready to be a supervisor a month from now? How can you use development to avoid turnover?

- For job positions with the biggest hiring need, develop some simple evaluation criteria. Anticipate and document how you’ll close performance gaps and how you’ll promote those who are excelling across the board.

- Hiring is harder than firing, so be thoughtful about termination. For the harder-to-fill positions, how deep are the employee’s deficits? What is the return on investment for developing that person instead? How much effort can you afford to spend in developing a poor or mediocre performer?

By the way, be on constant lookout for new hires you want to retain and/or cross-train after your demand surge subsides.

Impact on Culture

Every employee contributes to the culture, including the new hires. When you’re hiring thousands of people at one time, they have the potential to impact the existing culture. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, but no company wants to change their company culture unwittingly.

- Set the stage by showing a video on the company culture, purpose, vision, and values during onboarding.

- Enlist high-profile company leaders to visit facilities and personally welcome some of your new hires. A high touch “hello and welcome” is more meaningful than a big, impersonal all-hands. The new hires who speak to the leader(s) will tell other new hires of the gesture and that’ll strengthen engagement and loyalty.

- If the new hires are located together, physical reminders like posters and company gear such as caps or tee-shirts can reinforce the company culture.

- Invest more time with the coaches, team leaders/supervisors, to ensure they role-model the culture. They are the closest to new hires and their impact is huge.

- Identify a few key behaviors that are imperative to maintaining your culture/values and bake those into performance evaluations. Then act quickly to address those who are counter-cultural.

It’s daunting to hire thousands in a matter of months. Hiring the right people in the right numbers will answer your business demands and yield the outcomes you want, including revenue, profitability, and brand reputation. Invest a little to do it right.

Scale fast but scale smart.