One painful aspect of leading is firing people you like. It’s hard for many reasons. The employee may love working with you and for your company. It might be someone you are friends with outside of work. And they might just be a good person who is doing their best. Firing anyone isn’t easy but firing someone you like is especially difficult. Rather than face this head on, many managers avoid it, until it’s too late.

William (“Duffer”) Duff, who runs a successful San Francisco-based architecture firm faced this issue. He describes what happened after he hired a referral from a close friend:

“I was over-compensating for the previous person, who wasn’t good at the tactical, operational work. I was looking for a can-do person who wasn’t afraid of anything. And my friend’s referral was exactly that. My blind spot was that I needed a solution. I think that’s one of the hardest things in business — to say no to something you desperately need. You have to deliver on a project and you don’t have all the resources and you need a key person. And here’s a person who almost-kind-of-fits, and it’s so tempting to hire that person. It’s the worst thing you can do.

That person was here 3 ½ years and it was evident that it was a problem after a year a half. It’s like you’re hearing something you don’t want to hear. So I didn’t act.

Then people voted with their feet. I had seven people leave, over time, and they told me ‘I’m leaving because I can’t work with this person.’ I did all this rationalizing, thinking, well that person was part of the problem, too. I’ve found that one of the hardest parts of being a leader is to know when to make those decisions and execute on them — to stop wasting time.”

Who hasn’t been in this situation? The key is to identify signals that force you to examine what you’d rather not. Here are some clear indicators.

Their results are mediocre. Data doesn’t lie. If you are not seeing growth, that person isn’t solving the problem you hired them to solve. It’s easy to attribute causes to external factors but, ultimately, you need outcomes. If your conversations are about all the reasons that person can’t deliver, step back. These are excuses, not ownership and problem-solving. You have the wrong person. To paraphrase Jim Collins, the enemy of great is good enough.

You find yourself doing their job. They’re delegating to you. You’re reducing their load. It’s easier to do the job yourself. It starts subtly, but ultimately, you’re doing what you hired them to do. To state the obvious, one of you is redundant.

Their actions don’t reflect your values. Values define how you want people to behave. If that person behaves in a way that isn’t consistent with your values, they damage your brand for both employees and customers.

For Duffer, values are the litmus test. He explains his indicator this way.

William Duff’s key indicators.

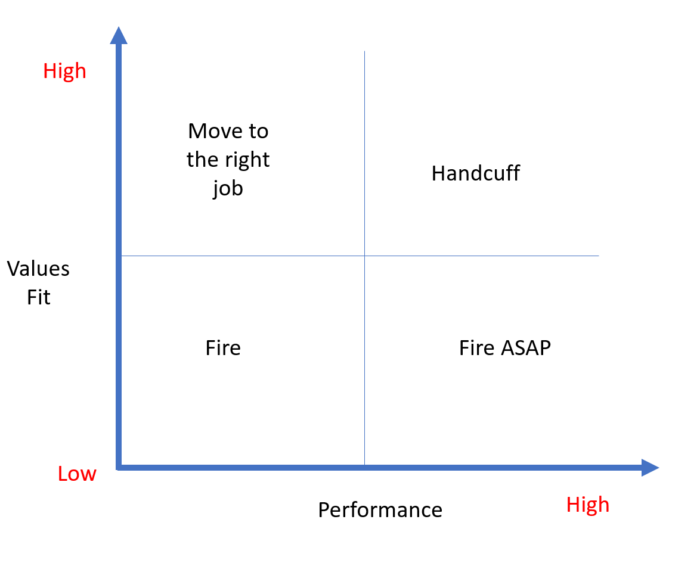

“The first time I saw the problem clearly was at an industry summit. The speaker, Cameron Herold, drew this box, and labeled it ‘Values and Performance’ and told us, write your people’s names on this grid.

“When we finished, he said, ‘So you have low values, low performance, what do you do?’ And I thought, duh, you fire them.

Then he said, ‘What if you have high performance, high values?’ And I’m like, well you handcuff them, don’t let them go anywhere.

Then he said, ‘What if you have low performance, high values?’ And I thought, I don’t know. He drew a chair and said, ‘You try to get him to another seat on the bus. Because maybe they are a good fit in the firm.’

Then he pointed to the bottom right and said, ‘What do you do down here — the high performance, low values person? Fire them ASAP. This is the cancer in your organization.’

I remember this viscerally because he had us write it all down. One of the names was a college buddy I had hired a year before, and it clearly wasn’t working. I crossed out my buddy’s name and moved it over. That’s how badly that I didn’t want to face reality. I was like, no, I misanalyzed that.

“Looking back, I shake my head. I had the answer right in front of me. Letting him go was a tough decision but ultimately the right one for both him and us. His values were mostly aligned but he was in the wrong seat on the bus and we didn’t have a different seat available for him. He’s now in a new job that’s much better suited to his skill set and, not surprisingly, is doing well.”

We like being liked. And we like to work with those we like. But some likable people can be harmful to your team and your organization. Identify your signals and check them often. You owe it to yourself, your company, and everyone you serve.